how Tyler, the Creator & Odd Future evolved and dominated the 2010s

“I created O.F. ’cause I feel we’re more talented than 40 year old rappers talking about Gucci,” Tyler, the Creator rapped on the title track of his debut mixtape Bastard, released on Christmas day in 2009, and it was as good a mission statement as any for what Odd Future (or Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All or OFWGFKTA) set out to do. They had an “out with the old, in with the new” mentality, and after Tyler’s late-2009 mixtape helped the group break through, they quickly proceeded to dominate the musical landscape of the 2010s and write their own rules while doing so. They released all their mixtapes for free on the internet before that became commonplace, they earned a reputation for rowdy live shows that were closer to punk shows than rap shows (before moshing was commonplace at modern-day rap shows), and they made their own raps, hooks, and beats that couldn’t have seemed to care less about the dominant trends in rap at the time. Their production could remind people of anything from Def Jux to The Neptunes, their egregiously offensive yet somehow effective shock factor recalled prime-era Eminem, and their anarchic crew mentality brought to mind the Wu-Tang Clan. But mostly, Odd Future seemed strikingly original right off the bat. It wasn’t clear in 2010 if they were built to last but it didn’t really matter. They came, they saw, and they shook up the world of overground and underground music upon arrival. As hooks like “Kill people, burn shit, fuck school” (from Tyler’s “Radicals”) made very clear, they were rowdy, they had a youthful sense of invincibility, and they simply didn’t give a single fuck.

The offensive shock factor, which relied heavily on rape jokes and homophobia including literally hundreds of usages of a certain homophobic “F-word,” was of course swiftly met with backlash, though Tyler and the rest of the Odd Future gang still somehow managed to captivate even many of the listeners who knew the lyrics were indefensible. Maybe it’s because it felt like there was real pain driving Tyler and his friends to come off so brash. Tyler framed Bastard as a therapy session and it opened with a confessional that tackled depression, self-harm, and Tyler’s fuming hatred for his absent father. The music felt so full of authentic, unfiltered emotion that somehow the pure offensiveness became an asterisk rather than an aspect of the music that would cancel Odd Future entirely.

It got harder and harder to defend, though, as Tyler refused to mature. Five years and three albums later on 2015’s Cherry Bomb, the Odd Future leader was still making poor excuses for his right to offend with cringeworthy lines like “Cabbage was made, critic f****** was shook / So I told ’em that I’ll exchange the word ‘f*****’ with ‘book’ / All them ‘books’ is pissed off and had their ‘page’ in a bunch / Fuckin’ attitude switched just like a ‘book’ when it struts.”

At the same time, other members of Odd Future (which gradually ceased existing as a group) became stars of their own, and, as fate would have it, Odd Future actually ended up launching the careers of some of the most prominent queer hip hop artists of the current decade. One of the true gems of the Odd Future mixtape era was the debut from an artist who wasn’t a rowdy, abrasive rapper but an experimental R&B crooner: Frank Ocean‘s 2011 tape Nostalgia, Ultra. It was an instant hit with the blogs and established Frank Ocean as one of the major forces in the then-developing “indie R&B” wave, alongside mixtape-era Weeknd, James Blake, How To Dress Well, and a few other key players. Frank would become an icon a year later, when he published a coming-out letter about his bisexuality and released his major label debut Channel Orange, an album indebted to the likes of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder that still stands tall as one of the finest albums of this decade in any genre. It made Frank a star, but unlike formerly likeminded contemporary The Weeknd, fame didn’t water down Frank’s music. He quickly rejected the restrictive expectations of major labels and the Grammys, and after a four-year album gap, he returned with the self-released Blonde and the video album Endless. They featured the most experimental songs Frank Ocean had ever written, and despite how inaccessible the music was (or because of it?), Frank Ocean became an even bigger, more beloved artist. He changed the game with each new album he released, he became a queer icon, and he infiltrated the mainstream as an ambassador for experimental music. Once “the R&B singer in Odd Future,” now one of the most definitive artists of the 2010s.

As it turned out, Frank Ocean wasn’t the only queer R&B singer to emerge out of the early Odd Future crew. Syd (fka Syd tha Kyd) started out as a DJ and producer for the group, she eventually formed the electronic duo The Internet with fellow Odd Future member Matt Martians, and The Internet eventually developed into a full band that, by 2015’s Ego Death, had released one of the finest neo-soul albums of this decade. By Ego Death, Syd had fully transitioned from her former role as background DJ to the role of frontwoman, and she only continued to break out from there. In 2017, she put out her debut solo album Fin which saw her veering away from The Internet’s warm neo-soul towards cold, metallic R&B. The following year, The Internet regrouped and released Hive Mind. Like Frank Ocean before them, they made a more difficult, less accessible album and it only helped grow their fanbase. It’s almost hard to remember the days when Syd wasn’t one of Odd Future’s biggest stars and The Internet was a low-profile offshoot of Odd Future. When O.F. set out to change the world with their skater-friendly mosh raps, I don’t know if anyone could’ve predicted they’d do it by establishing some of the decade’s most prominent R&B/soul artists with Frank Ocean, The Internet, and Syd.

Back in 2010 when Tyler was stirring up controversy, riding high off the success of Bastard, and driving crowds into a frenzy with pals like Hodgy, Taco, and Domo Genesis, Odd Future had another rapper garnering almost as much attention as Tyler but he wasn’t there to see it for himself: Earl Sweatshirt. Earl’s debut mixtape Earl came out just a few months after Tyler’s (and as song titles like “epaR” and “Wakeupf*****” made clear, he was just as involved in the offensive shock factor as Tyler was), and it was an instant cult fave. A lot of people considered Earl the most technically skilled rapper in the bunch. Earl, who was 16 at the time of the mixtape’s release, was kept away from the spotlight by his mother who sent him to boarding school as Odd Future began experiencing fame. His cult status kept rising, and chants of “FREE EARL!” became as much a part of Odd Future concerts as the music itself.

By the time Earl was back from boarding school and able to join his friends in the public eye, he was already a major label artist. He put out his proper debut Doris in 2013 and continued his reign as a growing star. Like Frank Ocean, fame had negative effects on Earl and that became obvious on his next album, 2015’s I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside. Right down to the title and the plain black artwork, it presented itself as an introspective, shy, pessimistic album, and it didn’t sound much at all like Doris (which, at this point, is Earl’s most mainstream-friendly release). In 2015, Tyler was churning the same shock factor-ridden gears as he was half a decade earlier and most of the other Odd Future rappers had fizzled out, but Earl was doing something new and different. I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside felt more like a bedroom singer/songwriter album in spirit than like a major label rap album, and it remains one of the most original-sounding rap albums released this decade. It’s arguably the most significant rap release that the Odd Future gang put out since Bastard, and it actually shares more in common with that album than most of what Tyler did post-Goblin. Like Bastard, it’s an album of raw, unfiltered emotion delivered over dark, trend-averse production from the same guy recording the raps. By the time Earl followed I Don’t Like Shit with last year’s Some Rap Songs, he had reinvented himself yet again and he had gone in an even more experimental direction. The whole album is less than 25 minutes long and it plays out like a collage of cut-up-and-stitched-back-together soul samples with hazy raps from Earl that are a far cry from the clear-eyed bars he rapped as a teenager. It sounds absolutely nothing like Earl, but it stays true to the mentality that Odd Future had back then. It does whatever the fuck it wants.

Earl, Syd/The Internet, and Frank Ocean all grew and matured fairly rapidly throughout the decade, even though they were all members of a collective who once seemed like “mature” was the last word they’d ever want anyone to describe them as. As those eyerolling lyrics on Cherry Bomb made clear, Tyler’s growing pains were a little rougher. He seemed intent on never growing up, but he was growing as a producer. The shock factor lyricism of Cherry Bomb may have been stale, but the inventive production was anything but. Now, Cherry Bomb comes off like a transitional album for Tyler. It sounds like he was stuck between his past self and the person he would start emerging as on his next album, 2017’s Flower Boy. The production on Flower Boy saw Tyler making yet another step forward, and one of its best songs, “I Ain’t Got Time,” included the first Tyler, the Creator lyric to turn heads in years: “I’ve been kissing white boys since 2004.” The internet quickly wondered: did Tyler just come out of the closet? Thinkpieces came pouring in, and many were quick to dig up a 2015 tweet that read “I tried to come out of the damn closet like four days ago and no one cared hahahhahaha.” Was Tyler, the man responsible for rapping the word “f*****” over 200 times on his debut album, actually queer this whole time? Or was he just, once again, trolling everyone? No one could really know for sure, and even if he was serious, did that make up for the countless derogatory comments he made in the past? Could it all be chalked up to insecurity and internalized homophobia? These are questions that may still all be unanswered, but one thing is for sure: respect for Tyler started to rise. Flower Boy became his most acclaimed album since his early days, and he started to emerge as an influential elder statesmen, including to prominent women and queer artists.

If you are feeling like it’s way too soon for Tyler to be considered an “influential elder statesmen,” consider that Kevin Abstract — leader of the massive rap group Brockhampton and one of the most prominent openly gay rappers active today — was in middle school when Odd Future first broke out. He since went on to say that they “laid the blueprint” for what Brockhampton would eventually become. Billie Eilish, possibly the most popular alternative pop breakout star in the world right now, hadn’t even turned 10 yet when the “Yonkers” video came out and when asked this year what artist she’s dying to work with, Tyler the Creator was the first name out of her mouth. Artists like Billie and Brockhampton grew up listening to Odd Future and O.F. shaped their lives the way an alternative rock band in the late ’90s or early ’00s would’ve had their lives shaped by Nirvana. With both Billie Eilish and Brockhampton releasing chart-topping albums in the past year, it would seem that Odd Future’s mission to change the music world was complete. In true Odd Future fashion, though, they are only just getting started.

Last month, Tyler released IGOR, which sounds like nothing else in his discography and which is easily his most essential album since Bastard. Fans and critics may have wondered if Tyler was trolling about his sexuality on Flower Boy, but it would be hard to wonder that on IGOR. It’s an earnest, tender album with lovesick songs like “A BOY IS A GUN” that see Tyler singing about romantic same-sex relationships with pure affection. It sounds so genuine that it would be hard to not take him seriously. There is still pain on the album like there was on Tyler’s early material, but he sounds — both musically and lyrically — like he reached the place he was trying to get to for a while. The forward-thinking production of both Cherry Bomb and Flower Boy seemed to be building towards the gorgeous instrumentals of IGOR, and Flower Boy‘s Frank Ocean and Steve Lacy (of The Internet) collaboration “911 / Mr. Lonely” now seems like the catalyst for this album. The soulful song was an outlier on Flower Boy, but it would fit right in with IGOR, which features Tyler (and an impressive group of collaborators including Solange, Santigold, Pharrell, Charlie Wilson, and more) singing more than rapping, and is closer to an experimental R&B album than to a rap album. There are precedents for rappers making musical transformations like this, namely 808s & Heartbreak by Kanye West (who appears on IGOR), so it has understandably not been tough for Tyler’s fanbase to embrace and latch on to the new sound. (As evidenced by his upcoming arena tour, he is more popular than ever.) But that doesn’t make IGOR any less of a triumph. It’s always a risk to make an entire 180 like this, and Tyler pulled it off. It’s his best album in years and his most stunning artistic achievement since he introduced himself to the world almost a decade ago.

Speaking of Steve Lacy, he also just released a new album — one week after IGOR — called Apollo XXI. Steve joined The Internet during the making of their 2015 breakthrough Ego Death, so he wasn’t one of the original Odd Future members, but he has emerged as one of the most crucial musicians in the extended Odd Future family. In addition to being a key member of The Internet and a ridiculously good guitarist, he made notable contributions to Kendrick Lamar‘s DAMN. (co-producing and singing on “PRIDE.”), Solange‘s When I Get Home (co-producing “My Skin My Logo” and singing on “Sound of Rain”), and perhaps most visibly, Vampire Weekend‘s Father of the Bride, on which he contributed to a handful of songs including the standout “Sunflower.” Apollo XXI, his proper debut album and the followup to his 2017 EP Steve Lacy’s Demo, has everything from percussive funk (“Playground”) to smooth soul (“N Side”) to flashy guitar solos (“Love 2 Fast”), and its centerpiece is the nine-minute “Like me,” featuring LA band Daisy. It’s an ambitious, masterwork of a song, and it doubles as a personal essay that sees Steve opening up about his own sexuality and reaching out a helping hand to anyone else struggling to do so. “I didn’t wanna make it a big deal, but I did wanna make a song, I’ll admit,” he says in the beginning of the song. “I just wanna, just see who can relate, who’s out there.” And on part one’s chorus, he asks, “How many out there just like me? How many work on self-acceptance like me?” It’s yet another recent example of an Odd Future-affiliated musician using their platform to embrace queerness and promote queer acceptance (within hip hop and the world at large), and coming out with a great song in the process.

—

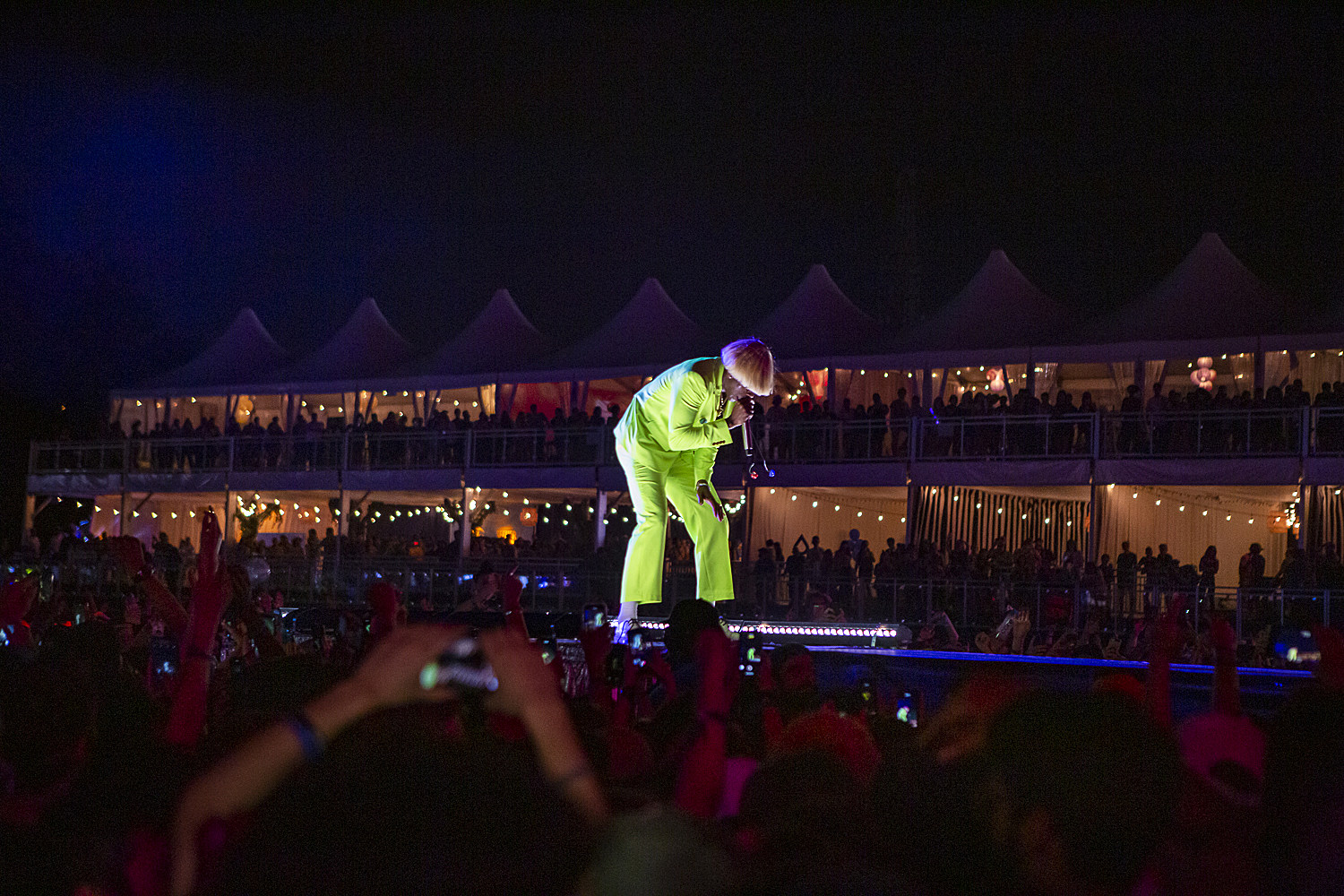

photos of Tyler at Governors Ball 2019 by Gretchen Robinette in the gallery above