your favorite David Bowie album based on your favorite genre of music

The late, great David Bowie was truly on a level that most artists — or people in general — can only dream of approaching. He truly did it all, and he never stopped doing it. From his early singles to his final 2016 album Blackstar, he has a half a century worth of music, most of it good, plenty of it great, and some of it out of this world. He was almost always ahead of the curve, constantly interested in what the next thing would be. (There are a handful of thinkpieces today suggesting that hip hop has surpassed rock in terms of creativity; Bowie said it in 1993.) Bowie helped create several styles of music, and for the ones he didn’t, he would often see new sounds emerging before they fully took off, and would quickly help shape those styles of music himself. There are hardly any subgenres of rock or pop music that Bowie didn’t have an impact on, and no matter what type of music you prefer — from the most experimental to the most pop — there’s probably a Bowie album for you.

Bowie never stayed in the same place for long and rarely repeated himself, and he was often very ahead of his time. Some Bowie albums didn’t really start to become influential until years or decades after their release. His entire oeuvre — which includes 25 studio albums, as well as several live albums, films, soundtracks, collaborations, visual art, and more — is worth consuming and could take a lifetime to fully do so. There are so many ways to break it down, and this list is just one of those ways. We’ve picked a selection of some of Bowie’s most memorable studio albums, and we’re presenting them not in any sort of order but in terms of which Bowie album would (probably) be your favorite based on your favorite genre of music. No Bowie album is ever just one genre of music, and of course your favorite genre of music could be metal but your favorite Bowie album is Low because we’re all complex beings and not just walking stereotypes, but I picked the albums and genres that I thought line up most neatly.

Read on for the list…

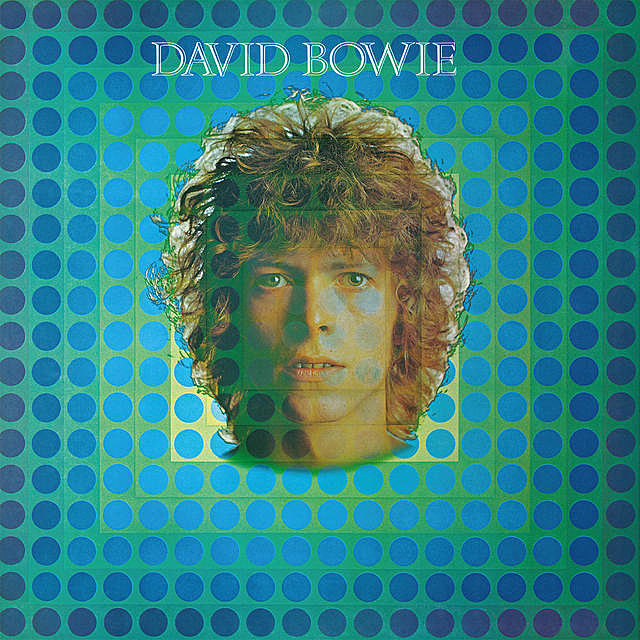

Psychedelic Rock – Space Oddity (1969)

Before Bowie became famous as a trailblazing glam icon, he — like a lot of artists who were active in the late 1960s — caught the psychedelia fever. His 1967 self-titled debut album is the kind of Sgt. Pepper’s-esque album that seemingly every British pop or rock artist made that year. It’s a better album than it often gets credit for being, but it wasn’t until his sophomore album two years later that he developed a sound he could truly call his own. The album — initially also self-titled but later retitled Space Oddity — is now best known for its title track, which didn’t actually become a huge hit until a few years after its release, but there’s so much more to Space Oddity than that one song. On this album, Bowie was still very much working within the realm of ’60s psychedelia, but he wasn’t copping anyone else’s style this time. The album’s full of lazy acoustic guitar strums, trippy effects, a nine-minute song, and album-closer “Memory Of A Free Festival,” which, with its repeated coda of “The Sun Machine is coming down, and we’re gonna have a party, uh huh huh,” is a certified hippie anthem. The songwriting is as strong and distinct throughout Space Oddity as it is on his more popular ’70s albums, but he favors bleary, meandering atmospheres in a way he stopped doing once the ’60s ended. And that’s why it’s the flower power hippie’s Bowie album of choice.

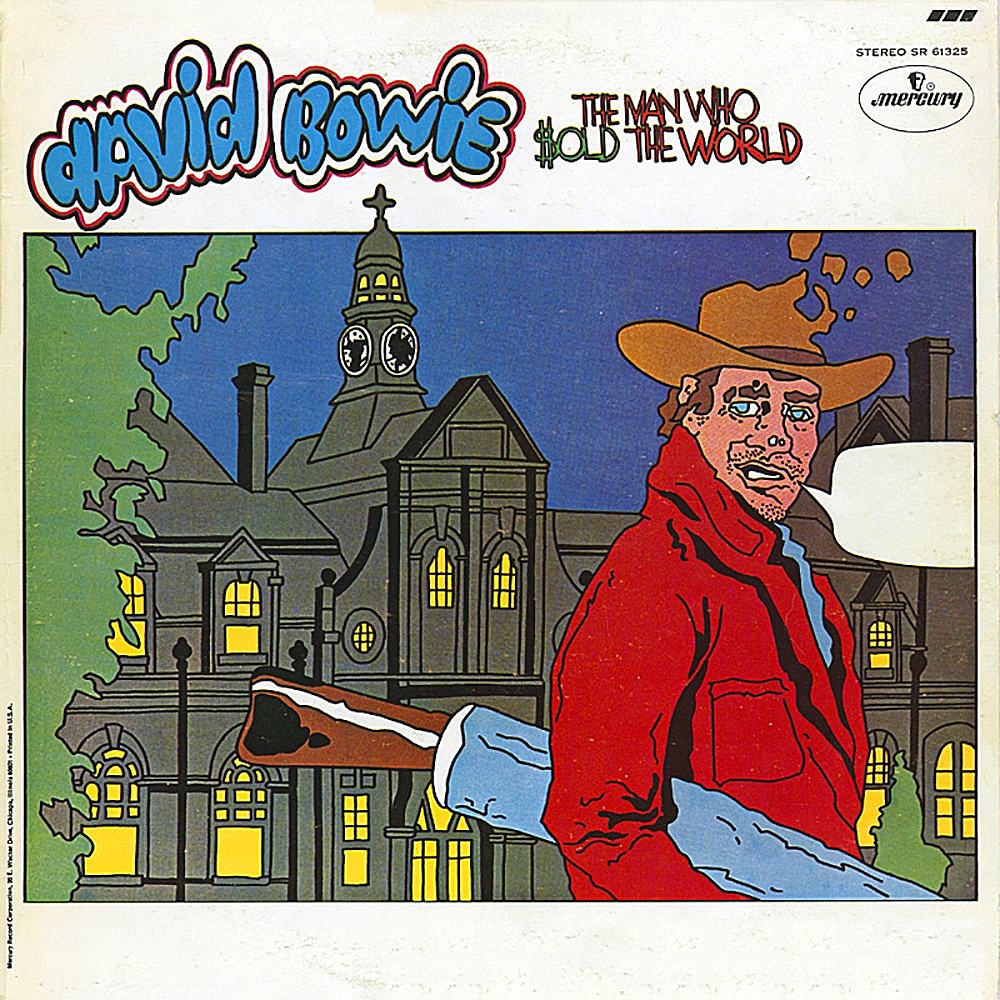

Metal/Hard Rock – The Man Who Sold The World (1970)

A lot of people know The Man Who Sold The World because of the Nirvana cover of the album’s title track, but Kurt Cobain’s love of that song isn’t the only reason why fans of heavier music would gravitate towards this album. The psychedelia of the ’60s hadn’t quite worn off for this one, but instead of flower power folk songs, this time Bowie channelled the kind of ’60s acid rock that morphed into what became known as proto-metal. And actually, the song Nirvana covered is one of this album’s lightest songs. The breathtaking, eight-minute album opener “The Width of A Circle” sees Mick Ronson bringing in heavier riffage and the kind of fuzzed-out solos that might qualify as “stoner metal” today. The same could be said of Ronson’s riffs on “Black Country Rock.” The undertones of parts of “All The Madmen” can be as doomy as some of the Black Sabbath songs from that same year, and there’s a little proto-doom/sludge on “Saviour Machine” as well. Perhaps the most overtly heavy song is the fuzz-drenched sludgefest of “She Shook Me Cold.” When you look at modern-day bands who fuse sneering, melodic vocals with doom riffs like Uncle Acid or sometimes even Arctic Monkeys, it’s hard not to look back on “She Shook Me Cold” as a clear predecessor.

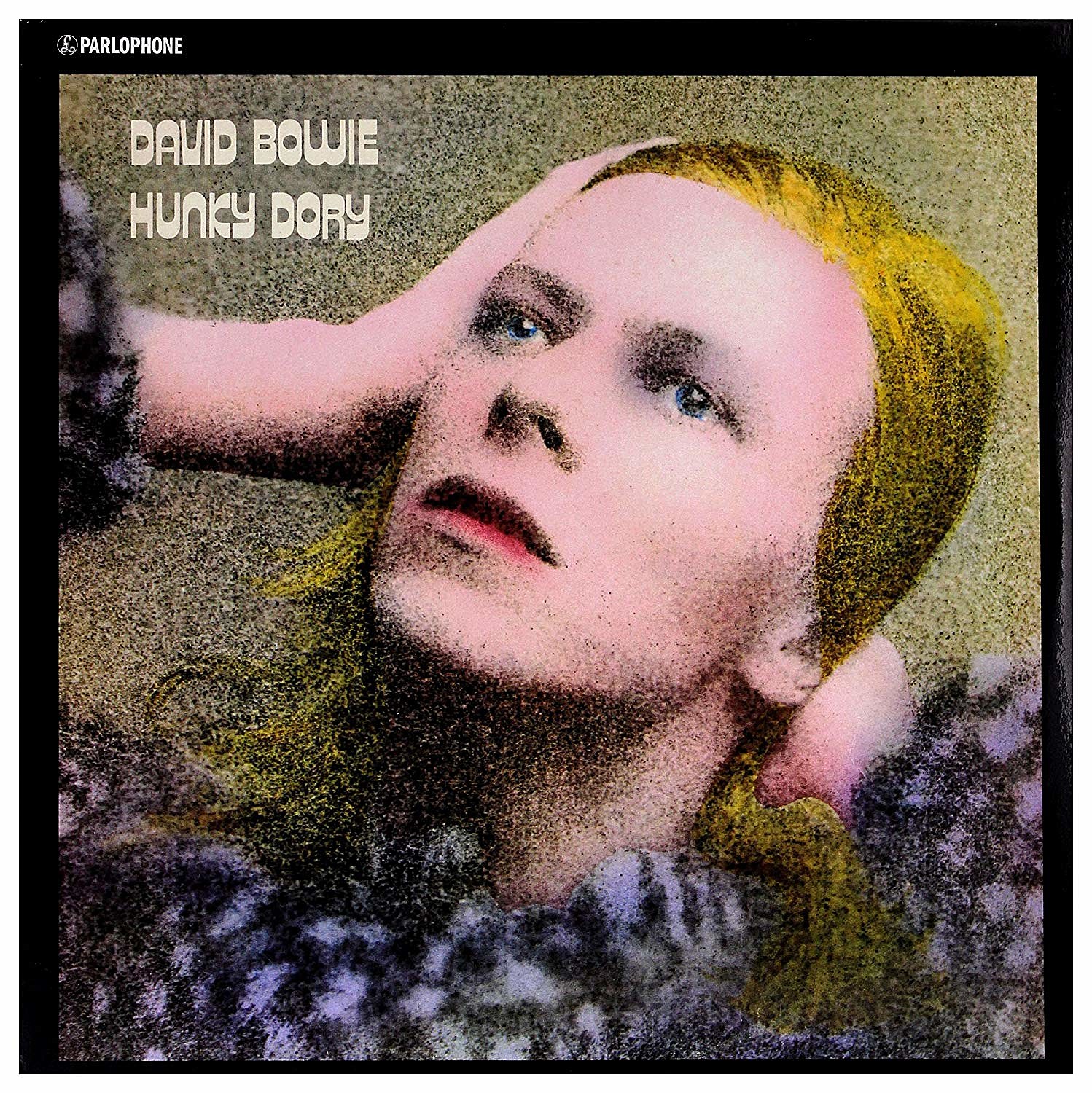

Glam – Hunky Dory (1971)

If you absolutely had to pick just one look and sound that Bowie is most famously associated, it would have to be glam. A handful of Bowie albums qualify as glam — including the iconic Ziggy Stardust (more on that soon — but the one that was glam through and through and solidified Bowie as one of the genre’s pioneers was Hunky Dory. It was released just a few months after Electric Warrior by T. Rex (who were friends/rivals of Bowie and who also worked with frequent Bowie producer Tony Visconti), and there’s a good argument to be made that those two albums went on to define glam as we know it. And for Bowie, it was really the first time he defined anything. He showed flashes of originality on Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold The World but was still mostly working within pre-established styles of music for both. Though Hunky Dory paid explicit tribute to ’60s icons with such songs as “Andy Warhol” and “Song For Bob Dylan,” the album musically left the ’60s behind and saw Bowie developing a sound that was new and hip and something he could fully call his own. Ziggy Stardust made him even more famous, but the glam sound of that album had already been fully realized on this one. Hunky Dory had everything — soaring string and horn arrangements, pounding piano pop, jangly acoustic guitars, rockers, ballads, you name it, not to mention great chorus after great chorus — all rolled into one sound that was greater than the sum of its parts. Even today, nothing on it sounds dated and there’s no song worth skipping. Bowie helped pioneer a genre and perfected it on the same album, and by the time the rest of the world started to catch on, he had already moved on to other things.

Punk – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

Bowie worked on three albums in 1972 that were crucial to the development of punk. He produced Lou Reed’s solo breakthrough Transformer and The Stooges’ most overtly proto-punk album Raw Power (not released until early 1973), and he recorded his own album about a fictional character named Ziggy Stardust, who was inspired by both Iggy Pop and Lou Reed. While Bowie’s influence on punk is undeniable, he never came nearly as close to actually writing punk music as he probably could have, but Ziggy Stardust, with its clear Lou Reed/The Velvet Underground and Iggy Pop/The Stooges influence, was the closest he did come. I think he was probably too naturally ambitious to ever make a record as simple and stripped-down as true punk, but Ziggy Stardust did a great job of marrying that ambition to music that had more than a little in common with The Stooges and The Velvet Underground. (Punk was also of course not fully a thing yet in 1972. By the time it was, Bowie was experimenting with all different kinds of stuff.) Ziggy Stardust shared a lot of qualities with its predecessor Hunky Dory, and Hunky Dory already showed off a clear Lou Reed influence with the song “Queen Bitch,” but “Queen Bitch” was just the tip of the iceberg compared to the punkness of Ziggy Stardust. From the unhinged way Bowie yell-sings at the end of album opener “Five Years” to the crunchy power chords that open “Moonage Daydream,” there are some proto-punk traits on the first half of the album — along with ballads and strings and all kinds of other stuff — but it’s really the second half of the album where things start sounding like punk as know it today. You could picture Iggy singing over the choppy power chords and fast-paced drums of “Star,” and with a little more distortion, the main guitar riff in “Hang Onto Yourself” could’ve become a Ramones song. The title-ish track “Ziggy Stardust” may have been more of a ballad, but the attitude in the chorus predicted punk’s attitude about as much as anything in 1972 could. The album’s punk peak, though, is “Suffragette City.” Up the distortion and lower the production value just a bit, and you’d have a song that could’ve fit on Raw Power. Leave it as is, and it’s still pretty punk. From the shouted “hey man!”s that punctuate the lines in the verses, to Bowie’s manic vocal delivery, to the song’s driving pace, just about everything about “Suffragette City” predicted the punk movement that was just around the corner at the time. Bowie ends the album with “Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide,” and by the time he’s hoarsely yelling at the song’s end, it’s very clear that this was the Bowie album early punk bands were taking notes from.

Krautrock – Station To Station (1976)

Bowie’s pop appeal stayed on a high for the three original studio albums that followed Ziggy Stardust, but by 1976’s Station To Station, Bowie started to let his freak flag fly more than he ever really had before. Bowie was a true original, but sometimes he was more of a great imitator than a great inventor, borrowing sounds he fell in love with from the (relative) underground and presenting them in a way the mainstream world could understand. He did it for The Stooges and The Velvet Underground on Ziggy Stardust, and on Station To Station he did it for krautrock bands Kraftwerk and NEU!. Influenced especially by Kraftwerk’s album Autobahn (and lots of cocaine), Bowie began favoring cold, dark sounds, hypnotic rhythms, and plenty of synthesizers, and he did it all while writing choruses you could still play on the radio. (The ten-minute title track manages to be one of Bowie’s weirdest songs and one of his catchiest.) He took these sounds in even more experimental directions on the “Berlin Trilogy” that followed, but the “Berlin Trilogy” albums had so much else going on too, while the tighter Station To Station fits more firmly within the world of krautrock. It also — like Hunky Dory — marks a time when Bowie hit the reset button on his career. Other albums had glam elements but Hunky Dory fully nailed it on the first shot, and that’s what Station To Station was for krautrock.

Indie Rock – Side A of Low (1977)

It’s probably easier to say which Bowie albums didn’t influence any indie rock bands than which did, but when people talk about the crop of indie bands like Arcade Fire and Wolf Parade that took influence from the Davids (Bowie and Byrne), the Bowie album they’re often talking about is Low. Like Bowie’s other 1977 album “Heroes,” Low is split into two halves: Side A (the rock half) and Side B (the ambient half, influenced by Brian Eno who worked on the “Berlin Trilogy” albums with Bowie). Side A is rawer and weirder than 1976’s Station To Station, but the songs are also shorter and more rock. It was perhaps also influenced by punk, which exploded in 1977, but these songs weren’t driving like the Ziggy Stardust songs often were. (“Breaking Glass” is at least sort of post-punk though.) These songs are quirky and upbeat and too challenging to be pop songs but strangely catchy anyway — just like indie rock in the ’90s and ’00s was. And not only is Low clearly influential on indie rock bands, it’s also the indie rock fan’s Bowie album of choice because it’s exactly the kind of album indie rock fans like. It’s one of his less popular albums, but the kind of album that diehards will defend to the death, the same way that, like, indie rock fans will tell you Neutral Milk Hotel made a better album in 1998 than Madonna did. The indie rock way is to be anti-mainstream but still write catchy songs in your own, weird way. And that’s what Low is.

Ambient/Post-Rock – Side B of Low (1977)

Not only was Bowie making krautrock and weird, proto-indie rock in the late ’70s, he also fell in love with Brian Eno’s ambient music and he ended up collaborating with Eno on his “Berlin Trilogy,” which included his two 1977 albums (Low and “Heroes”) and 1979’s Lodger. The first two of those albums had pop songs (umbrella term) on side A, and ambient songs on side B, while both are equally important and influential, I’d have to still pick Low if forced to pick one Bowie album for ambient music and post-rock fans. Eno was of course a major player on this album and his own music is of course even more influential than Bowie’s on these genres, but when you listen to the second half of Low, you can hear the seeds being sown for anything from late-period Talk Talk to Sigur Ros to Kid A to Four Tet to Grouper. Those are all mostly modern acts, and side B of Low still sounds as fresh today as those artists do. There were of course other artists experimenting with space and ambience before Bowie made Low, but the album still manages to sound ahead of its time today. It’s some of his most unapproachable music, but also some of his most timeless.

New Wave – Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980)

From his glam songs to his proto-punk songs to his art-funk songs to his kraut/synth songs, Bowie was a massive influence on the early new wave bands, so it only made sense that Bowie was able to easily pull off an album of his own that fit relatively neatly into new wave. Following the more experimental “Berlin Trilogy,” Bowie went back to a more pop sound for Scary Monsters, utilized plenty of synthesizers, and nailed the perfect balance between his upbeat, funk-inspired side and his punkier art rock side. That’s sort of just an extra wordy way to break down what a lot of new wave sounded like, and you don’t even need fancy descriptions to explain why this album fit in perfectly with the new wave bands of the era. Singles like “Ashes to Ashes” and “Fashion” were about as new wave as it gets. Bowie was far from the only ’60s-era rocker who started embracing sounds like disco and synthpop in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but while a lot of those other rockers were met with backlash, Bowie pulled it off as naturally as humanly possible. He was a great ’60s psychedelic artist and also a great ’80s new wave artist. The same human is behind it all, but the Bowie behind Space Oddity and the Bowie behind Scary Monsters are two entirely different Bowies, and both are equally authentic. He progressed at the speed of light and changed it up from album to album throughout the ’70s, but it was really on Scary Monsters that it became so clear how chameleonic he could be. A lot of transitional stuff happened within music during the ’70s, but the ’60s and the ’80s feel distinctly separate, and Bowie will forever be tied to some of the hippest, most forward-thinking sounds of both decades.

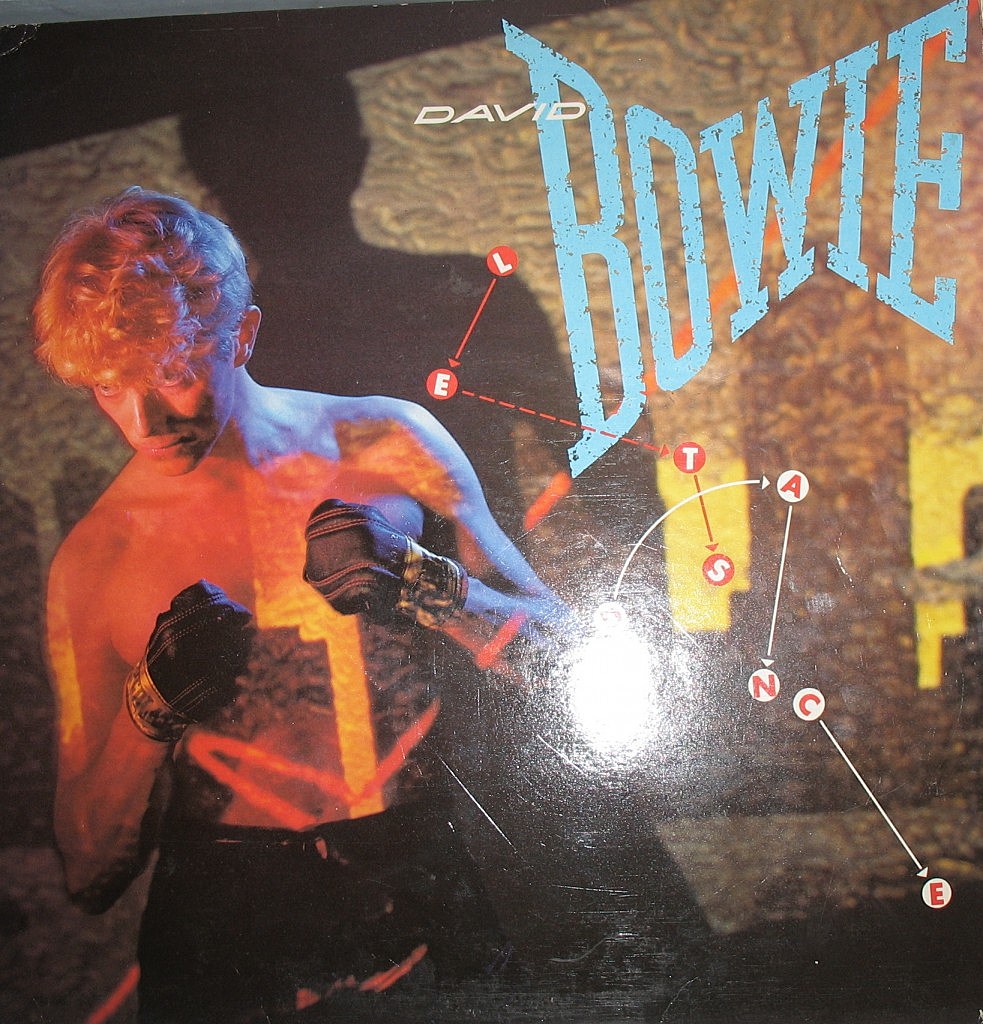

Pop – Let’s Dance (1983)

After Scary Monsters sent Bowie skyrocketing into the ’80s with a fresh, synthy pop sound, Let’s Dance made him a bonafide ’80s pop star. As fantastic as Bowie’s ’70s work was, he hadn’t really crossed over as a pop star in the US yet. 1975’s “Fame” was a No. 1 hit over here, but otherwise he didn’t fare too well on the US charts until 1983’s Let’s Dance. Its title track became Bowie’s second No. 1 hit in the U.S. — with “Modern Love” and a reworked, slicked-up version of “China Girl” (which Bowie had previously co-written for Iggy Pop’s 1977 album The Idiot) not far behind — and it made Bowie more omnipresent in the States than he had ever been before. He worked on the album with Nile Rodgers, who was already a hitmaker thanks to his band Chic and other disco songs he co-wrote like Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” and Diana Ross’ “I’m Coming Out” and “Upside Down,” and together, they came out with the most purely pop album Bowie had ever made. The success of Let’s Dance quickly led to Madonna asking Nile Rodgers to produce her 1984 album Like A Virgin, and you can instantly hear how some of Let’s Dance influenced the sharp pop of that Madonna album. And its influence continued to live on within pop music for decades, still being felt today via artists like Janelle Monae and Lady Gaga. As pop music often is, Let’s Dance sounds a lot more dated today than, say, Low. But with the massive ’80s influence that still exists within today’s pop, you could probably still sneak a song like “Let’s Dance” or “Modern Love” or “Shake It” on the radio today without raising too many eyebrows.

Industrial/Trip-Hop – Earthling (1997)

Let’s Dance may have made Bowie a pop star, but he didn’t adjust super well to the new attention and expectations, and followed that album with what he thought his new fans might like, only to later regret the decision. Towards the late ’80s, he started getting back to his more experimental roots, and in the ’90s he fell in love with the industrial and electronic sounds of the era. He started flirting with those sounds on 1995’s Outside, but really mastered it on 1997’s Earthling. Unlike Bowie’s experiments with proto-punk, krautrock, ambient music, and new wave, industrial was well-established by the time Bowie mastered it. Nine Inch Nails already brought industrial into the mainstream with 1994’s The Downward Spiral before Bowie even released Outside (and took NIN on tour with him to support that album), but it wouldn’t be fair to slight Bowie just because he wasn’t early to everything, and it’s pretty impressive to think he latched onto industrial at all. Not many ’60s-era rockers can say the same for such a forward-thinking ’90s phenomenon. It probably helps that Nine Inch Nails had a direct impact on Earthling — Bowie was fresh off collaborating on stage with them during the Outside tour and Trent Reznor did a remix of Earthling‘s “I’m Afraid of Americans” — but it’s still saying something that Trent Reznor remained a supporter of this album and still performs “I’m Afraid of Americans” at NIN shows today. That song is undeniably awesome, a true classic of the industrial era, and it’s not the only good thing about Earthling. Several songs on Earthling make use of breakbeats that find the middle ground between The Downward Spiral, drum n bass, and Portishead, and it’s still a thrill to hear Bowie’s voice over stuff like this. Some of these very ’90s sounds quickly became dated, and Earthling isn’t immune to sounding like a product of its time, but there are gems like the haunting “Telling Lies” that would still be a big deal if they came out today.

Jazz – Blackstar (2016)

Leave it to David Bowie to keep reinventing himself almost literally until the day he died. His final album, Blackstar, came out on his 69th birthday, and he would sadly pass away two days later. There is still some uncertainty as to how accurate it is that Bowie knew it would be his last, but even if he didn’t, he knew he was ill and the album clearly took some inspiration from knowing the end was near. And whether or not Bowie planned a followup, he made sure he would go out with at least one more forward-thinking instant-classic. Blackstar followed 2013’s The Next Day, which was one of the only times in Bowie’s career that he looked backwards (both the album artwork and the music were homages to the “Berlin Trilogy” era), and The Next Day was Bowie’s first album in a decade, following two just-okay albums in the early 2000s. But Blackstar was like nothing he had ever done before. It isn’t full-on jazz, but he made it with a group of jazz musicians including saxophonist Donny McCaslin who he came across at a jazz club in New York City. Bowie also said that he took inspiration from Kendrick Lamar’s jazz-heavy To Pimp A Butterfly, and Blackstar works jazz into experimental rock similarly to the way TPAB works jazz into modern-day hip hop. Blackstar doesn’t actually sound anything like To Pimp A Butterfly, but as Bowie had done several times before, he became fascinated with a new, forward-thinking album and it quickly caused him to approach his own music differently. Blackstar is like nothing else in Bowie’s discography, and when it came out, it wasn’t like much else in general. Only recently has its influence begun to show up on other albums, like Nine Inch Nails’ Bad Witch and former Talk Talk bassist Paul Webb’s new Rustin Man album Drift Code. Once again, Bowie was ahead of his time. If only he was still around to see his final impact.